Poetry Books

The Aardvark Venus: New & Selected Poems 1961-2020

Hermaphropoetics: Drifting Geometries

Out of Ur: New & Selected Poems 1961-2012

Solitary Workwoman

Luca: Discourse on Life and Death

New and Selected Poems 1961-1996

Rubbed Stones

Black Chalk

How Much Paint Does the Painting Need

W. C. Fields in French Light

Constructs

The Joe Chronicles Part 2

Shemuel

The Joe 82 Creation Poems

I Am the Babe of Joseph Stalin's Daughter

Salt and Core

Not Be Essence That Cannot Be

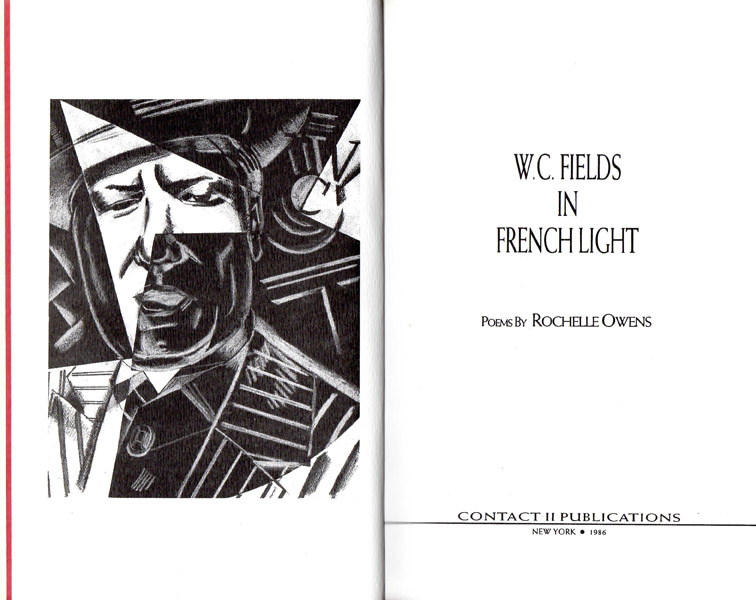

W. C. Fields in French Light

1986, Contact II Publications

Contact II Publications is proud and delighted to release Rochelle Owens' newest book, W.C. Fields in French Light, a two-poem opus bursting with vigour and charm. Ms. Owens examines life as an astronomer gazing into the vast twilight sky, poring over details with a painful honesty, yet never losing sight of the greater universe which her expansive view transforms into a celebration of poetry and life. As the Village Voice proclaims: "The shining energy, the music, the grandeur are in the writing itself, at once obsessed, knowing, flamboyant and concise."

Taking the best from the American literary tradition, from Walt Whitman to William Carlos Williams, Ms. Owens entwines us with an epic style, remaining fully aware of the contradictions that afflict our poetic heritage and our nation. W.C. Fields is invoked as mythologized savior, leading us through the American poetic landscape:

You're a myth

and I intend

to utilize you.

By cross-cutting culturally and inter-continentally, a whirlwind journey taking us from the glamor of W.C. Fields to the intimacies of W.C. Williams, from Nez Perce Indian massacre site to French countryside, Ms. Owens fulfills wonderfully Jerome Rothenberg's description of her as a "great tribal and primitive poet," able "to change public and private histories into primal myth." The myth of W.C. Fields; the myth of W.C. Williams; her search for literary truth in an age of untruths and doublespeak. The chanting, almost spoken quality of these poems builds like musical movements in successive waves, ultimately overwhelming us with awe.

The 11th book of poems by this poet and playwrite is a series of related poems—really a single long poem—exploring the poet's personal history and shaping it in the context of myth. Line by line, image by image, it is an ambitious work in design and invention. The texture is surreal, "A fragment catalog paste-up/of the 20th century/a time lapse/a naive father allegory" intertwining several motifs which don't coalesce into the kind of popular unified statement we see in much current poetry, but instead are held together by recurrent themes and the considerable power of voice.

It is an exploration of sources, where the persona is by turn "the woman as wrongly treated/as the Nez Perce Indian," "the lonely poet" who "speaks into the darkness/in the voice of W.C. Fields," "The tramping American/revolutionary," W.C. Williams' Flossie, at least indirectly Williams himself, "a whore/wearing a hat with oriental frankincense/and money tucked/in the seams/ ... a singing sailor in jail ... /a poor cowboy," and "Hamlet of Brooklyn"; in short, the Whitmanesque American Everyman, 1980's version.

Owens resists Whitman's penchant for the grandiose, however, preferring instead a rhetoric that takes into account the complexities of experience, and renders them convincingly. For her, poetry is "the essential nucleus/of the sphere of human/existence"; and not surprisingly a central aspect of her experience is her relation with language and imagination: "The text is behind/the revolution/desperate with imagination/eyelids, the bodily organs,/analytic, figure-making/The solid family-tree." The ongoing work is the difficult coming to terms with the sprawling landscape these elements inhabit: "My voice is a prolonged/ muscular twitch thick/as an elephants trunk/When will I develop/into a form?"

There's no real answer to that question, nor any resolution to the difficulties the poem engages, except the poem itself. It can be a frustrating condition; but that, as they say, is life—which is what the best poetry always is. This is genuinely interesting and challenging work; it deserves more attention than it will probably get.