Poetry Books

The Aardvark Venus: New & Selected Poems 1961-2020

Hermaphropoetics: Drifting Geometries

Out of Ur: New & Selected Poems 1961-2012

Solitary Workwoman

Luca: Discourse on Life and Death

New and Selected Poems 1961-1996

Rubbed Stones

Black Chalk

How Much Paint Does the Painting Need

W. C. Fields in French Light

Constructs

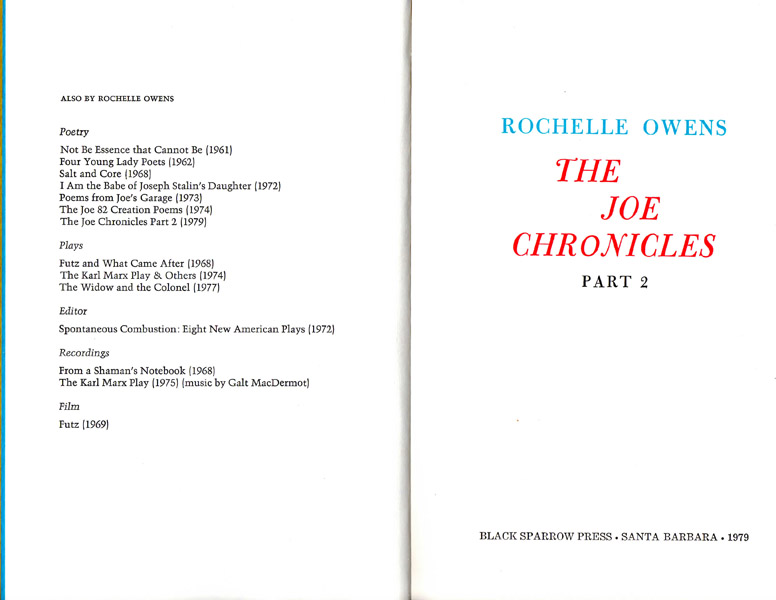

The Joe Chronicles Part 2

Shemuel

The Joe 82 Creation Poems

I Am the Babe of Joseph Stalin's Daughter

Salt and Core

Not Be Essence That Cannot Be

The Joe Chronicles Part 2

1979, Black Sparrow Press

ROCHELLE OWENS: THE POET AS PROPHET

Rochelle Ratner

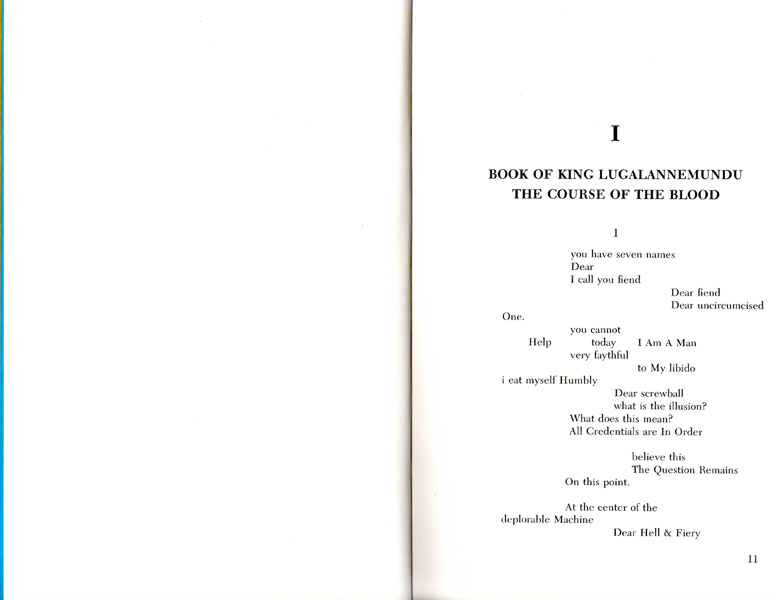

As an introduction to Shemuel, Rochelle Owens states that: "Imagination is the generator of the word as act/event. In Shemuel the journey begun in The Joe 82 Creation Poems and The Joe Chronicles, Part 2, continues to explore through patterns of force the conjunction of the old and the new, the spiritual and the physical." Over the years, Owens is slowly developing a major work in several volumes, of the nature and scope of Ezra Pound's Cantos, Charles Olson's Maximus Poems or Diane DiPrima's Loba, but from a very Jewish (Hebraic) viewpoint.

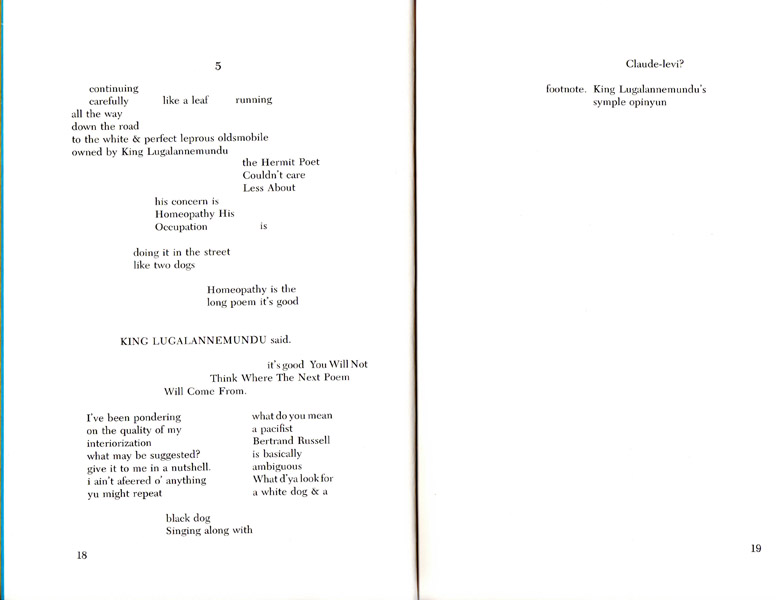

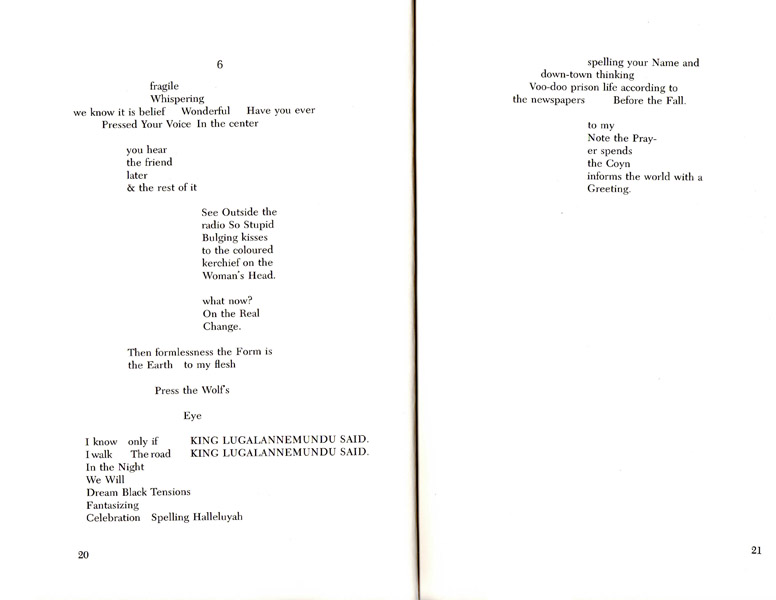

Also an accomplished playwright, Owens shows her sense of action in the motion of these poems on the page. Lines wave back and forth, at last becoming regular and motionless, as in the end of the whirling dervish ceremony, where the speaker is centered on his own ground, the voice almost tender compared to the hard-edged and often erotic images that began the poem. It's the tender moments in these poems, or in certain whole poems (such as No. 35 or No. 47 in The Joe Chronicles) which I feel show Owens at her best:

the Noah's ark

of your bones

pleases me

I remember first

your nose-jewel

glinting

like the ruby rain blood

of the crucifix

sit across

from me

& the heart

will tremble

from the grin

of king lugalannemundu

(from No. 47)

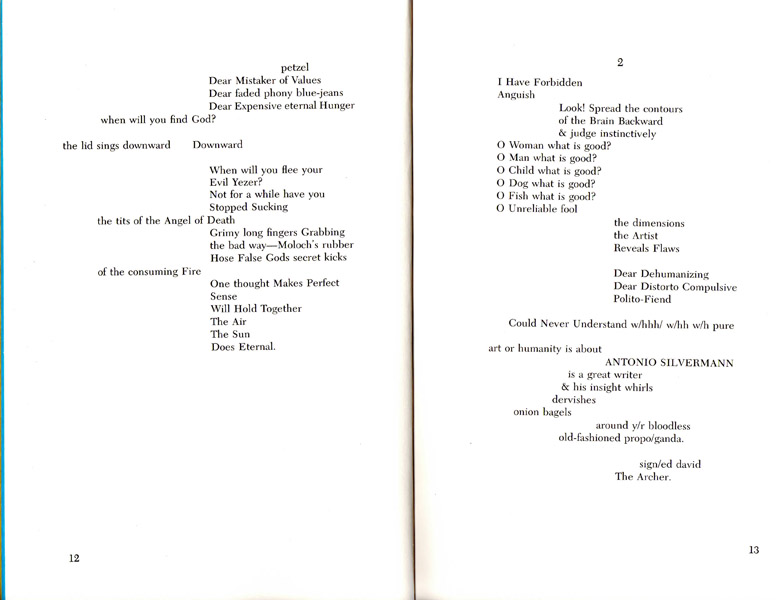

Owens is undoubtedly aware of the dervish ceremony and the mysticism supporting it, as she is aware of cabala, alchemy, homeopathy, Egyptian and Babylonian creation texts, the Old Testament, etc. So much of what she's giving us is an esoteric shorthand that the reader could easily overlook, as in her continued use of the phrase Evil Yezer (her translation of the Hebrew yetzer hara, or evil impulse) which she says is "just killjoy Frightening Us." Even without a complete understanding, the poems have an increasing power and a very definite humor.

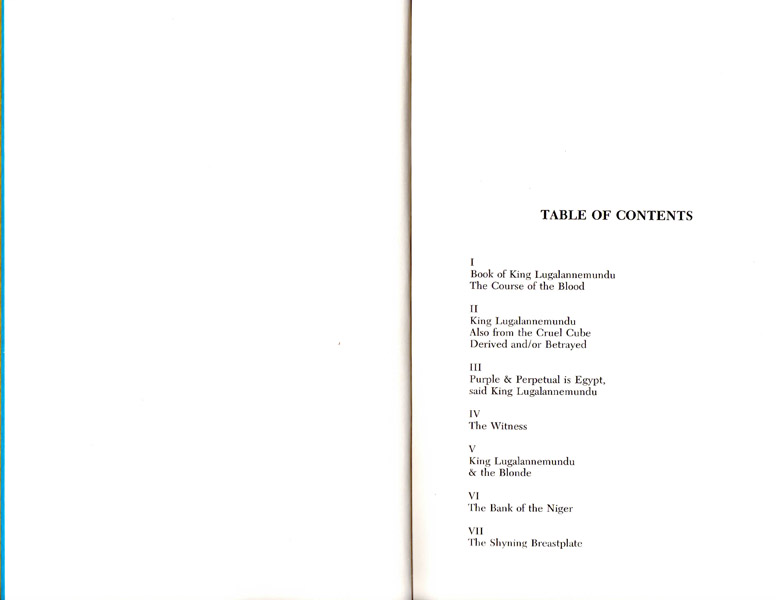

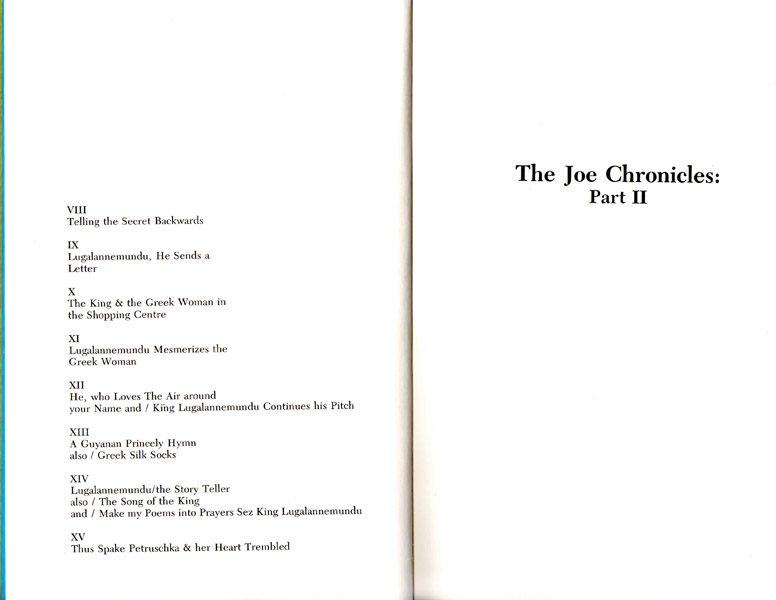

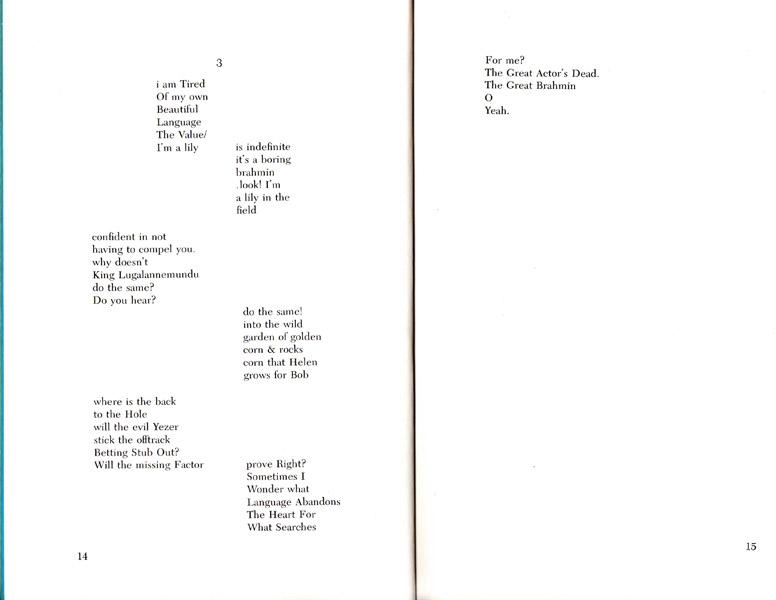

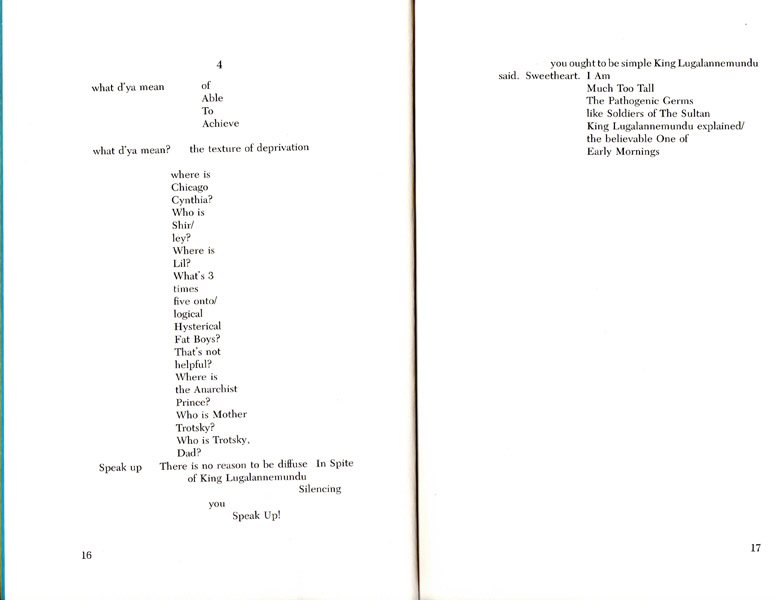

From various poems, we are given to understand that king lugalannemundu, the major character in The Joe Chronicles, is: a Christian boy or prince from Guyana (born for the joys of this world and who loves carp and red beets) who is courting various women (including a blond, a Greek, a housewife from a supermarket). Both the women and the poems are meant to transform him (and at the same time themselves and each other). The poem is the breath in his throat. More importantly, this is a man any man, in search for himself. Phonetic (mock-ancient) spellings and line breaks in the middle of words seem arbitrary and add to the confusion, but the voice transcends them.

"Joe's city is new york," she tells us in No. 64 of the Shemuel poems. Other poems in this book (which is most directly related to the Old Testament) describe the men, the city without god, the god taking revenge. She never lets us forget that she's a woman in the midst of 20th-century America. This reminder works better in some poems than in others and on the whole is much more natural to the poems in Shemuel than it is in The Joe Chronicles. Perhaps that's because Shemuel is the latter of the two books, or because the female voice here forces Owens to speak more directly in her own voice. There's a definite political consciousness, but it's all "anti" positions, all government ridiculousness—in fact, all governments—seem the same and are thus interchangeable. This is emphasized by the fact that often she doesn't use sentences, just somewhat wild (but not random) juxtapositions of words and phrases.

Owens' use of images is so casual that often we don't realize how startling her perception is until the same image repeats in a slightly different fashion several pages later. Individual lyrics mount to form a narrative. "Make my poems into prayers," king lugalannemundu says. For Owens, one cannot be a poet unless she is also a psalmist or holy singer.