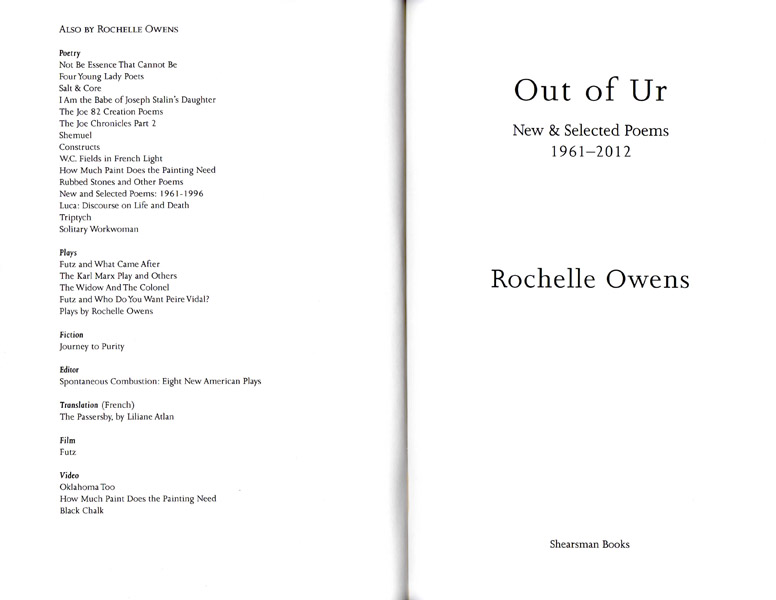

Poetry Books

The Aardvark Venus: New & Selected Poems 1961-2020

Hermaphropoetics: Drifting Geometries

Out of Ur: New & Selected Poems 1961-2012

Solitary Workwoman

Luca: Discourse on Life and Death

New and Selected Poems 1961-1996

Rubbed Stones

Black Chalk

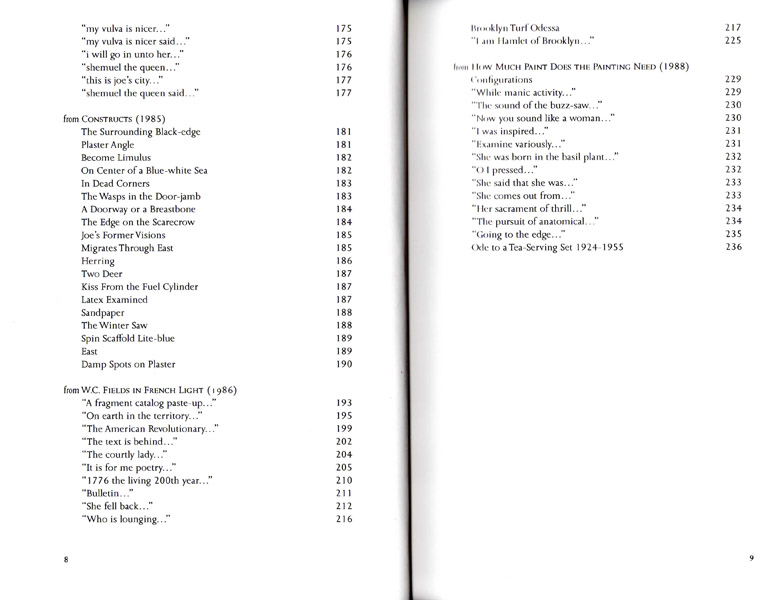

How Much Paint Does the Painting Need

W. C. Fields in French Light

Constructs

The Joe Chronicles Part 2

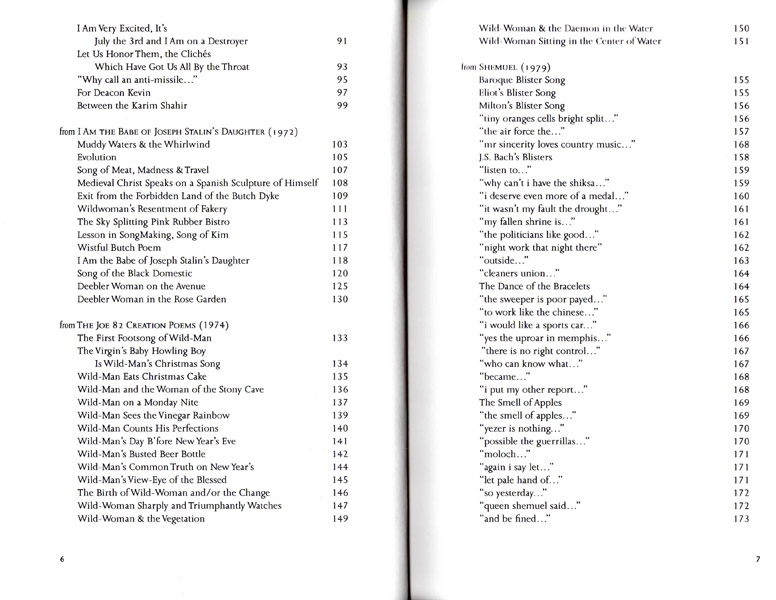

Shemuel

The Joe 82 Creation Poems

I Am the Babe of Joseph Stalin's Daughter

Salt and Core

Not Be Essence That Cannot Be

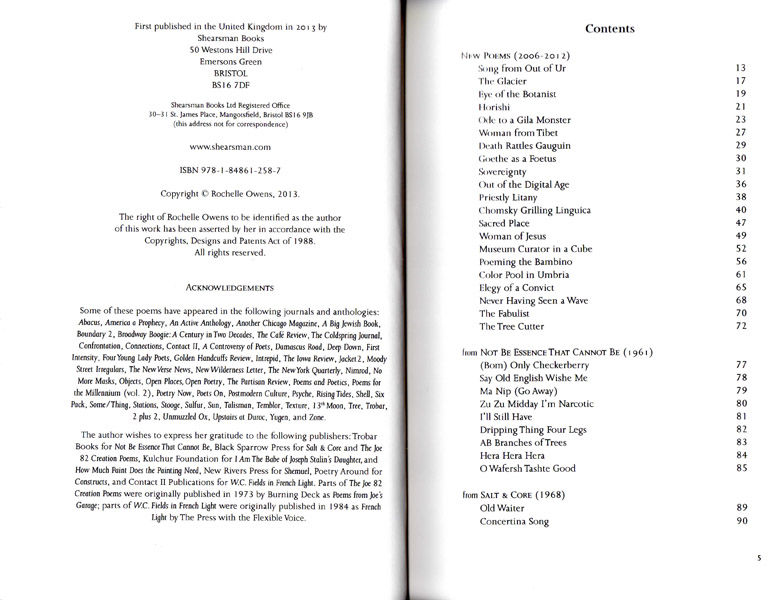

Out of Ur: New & Selected Poems 1961-2012

2013, Shearsman Books

"Out of Ur" New & Selected Poems 1961-2012 spans more than five decades of Rochelle Owens' innovative, influential and controversial work, and displays an extraordinary range of style, tone and experiment that is multigenre and multivocal.

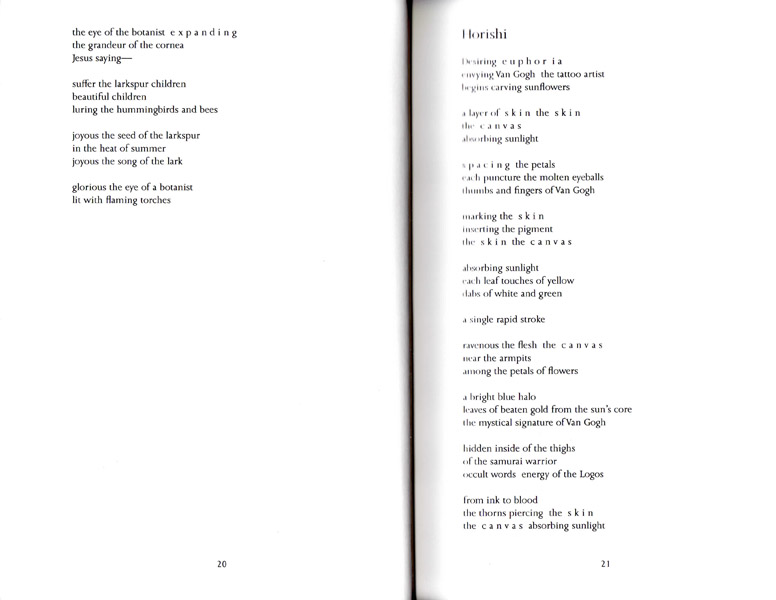

The recent poems take on many poetic tropes—vision, sight, imagery, imagination—and physicalizes them: we are not merely thinking, imagining beings, we are eyeball, abdomen, sphincter, skin, flesh, blood: the mammalian body and brain. To seek beauty can be a ravenous, painful quest—akin to carving into flesh.

The signature gesture that ties all of Owens' work together is a continual inventiveness—a direct and challenging encounter with language. It is a focus on the concreteness of words, the typographic texture, an insistence on language as material.

I dreamed of a birdwoman. A fantastic creature with a human body and the head of a bird. She fed her young with chunks of flesh that she savagely tore out of her body with her beak. Always the flesh grew quickly back so that there was no loss or end of herself. (R.O.)

There is a voice in Owens' work that seemed to some of us—when first heard—like a fierce & unrelenting force of nature or like that, more aptly, of some biblical Isaiah or Devorah, or of some other cracked (but real) Prophet mockingly come back to life. "Beauty will be convulsive or it will not be," André Breton had written in setting the Surrealist agenda, by which he meant (or we do) not beauty so much as poetry, with regard to which beauty is but one half (at best) of what we put into our workings. And Owens—while she proclaimed herself, New York style, as "simply a poor working girl [from Brooklyn] who was not even a graduate of Brooklyn College or C.C.N.Y."—spoke a language even in her first poems ("Hunger / It is luck too. Hullabaloo Vishnu") that called forth voices (Ball or Khlebnikov or Tzara) from a recent past that she & we were newly claiming, making into our present. With her base in poetry, she came to a first public recognition through a series of plays (Futz, Beclch, He Wants Shih, The Karl Marx Play, others), to create what one of us would call "her theater of impulse" & to make her for a time "perhaps the most profound tragic playwright in the American theater" (Ross Wetzteon, The Village Voice). What she had tapped into in herself were the sources of tragedy in ancient "goat-song" (pace Aristotle): a deliberate but disruptive mode of poetry, moving from what Toby Olson describes as "the grating nature of the inappropriate" to what he & Jackson Mac Low both speak of as "controlled hysteria." Writing further of the intelligence—as well as passion—that drives her work, Mac Low says: "I mean ... by 'controlled hysteria' ... that the speaker, whether the poet, a persona, or a blend of both, while often incredibly vehement, threatens to cross over the line from vehemence to uncontrollable emotional outburst, but never actually crosses that line. This arouses a feeling of suspense even in those who do not realize whence that feeling arises: a very 'theatrical' experience." That it also arouses—in us—a feeling of uncontrollable laughter is the further, maybe deeper secret of her art.

[Commentary from Poems for the Millennium: The University of California Book of Modern & Postmodern Poetry, volume 2, 1998.]

Source: Poems and Poetics