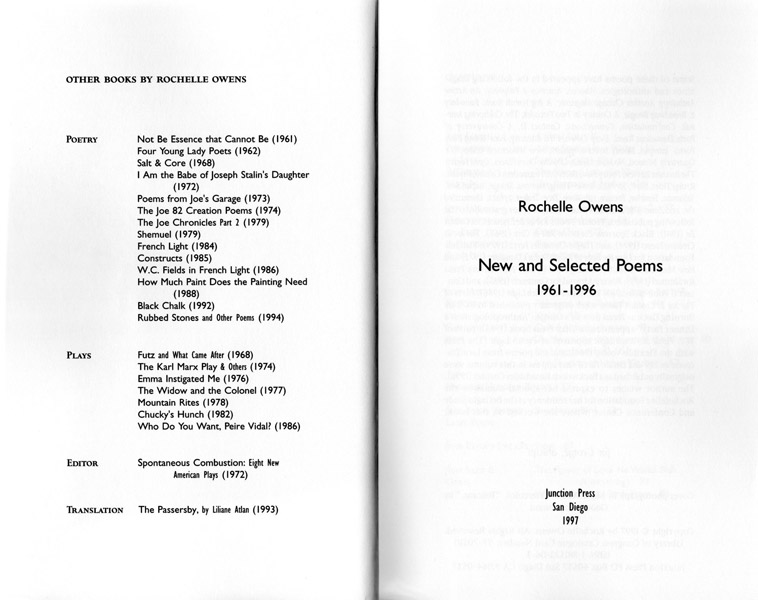

Poetry Books

The Aardvark Venus: New & Selected Poems 1961-2020

Hermaphropoetics: Drifting Geometries

Out of Ur: New & Selected Poems 1961-2012

Solitary Workwoman

Luca: Discourse on Life and Death

New and Selected Poems 1961-1996

Rubbed Stones

Black Chalk

How Much Paint Does the Painting Need

W. C. Fields in French Light

Constructs

The Joe Chronicles Part 2

Shemuel

The Joe 82 Creation Poems

I Am the Babe of Joseph Stalin's Daughter

Salt and Core

Not Be Essence That Cannot Be

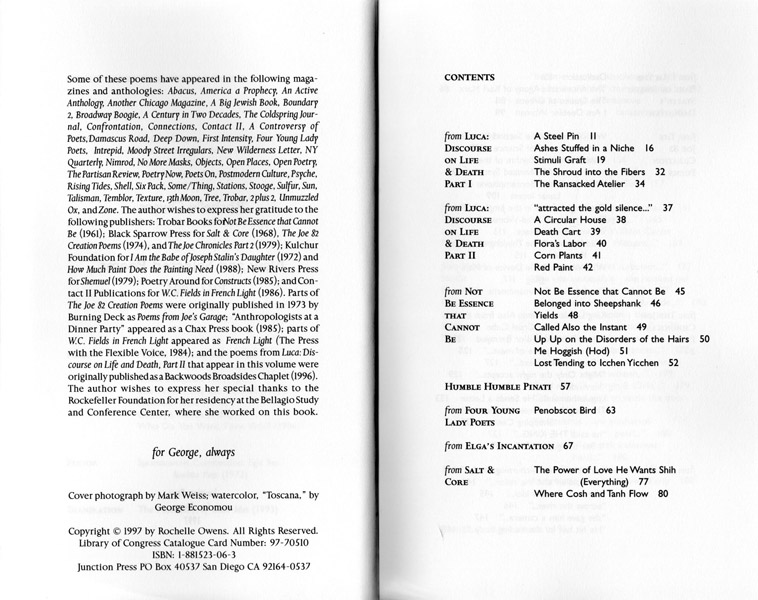

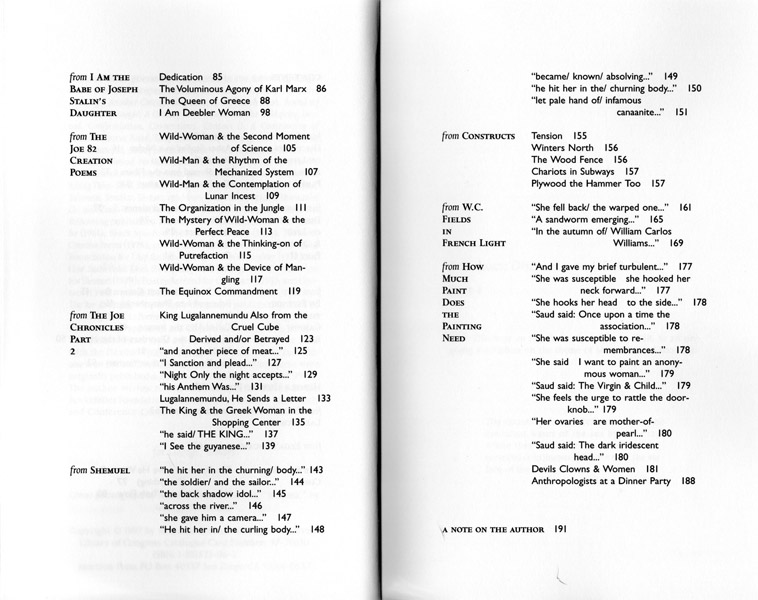

New and Selected Poems 1961-1996

1997, Junction Press

The range of experimental work in Rochelle Owens' New and Selected Poems is intriguingly difficult to categorize. While Owens' concern with the problem of women's socialization indicates a feminist component, gender is never a master-category in the poems. Her fascination with the materiality of the signifier and her staging of a multiplicity of "voices" suggest affinities with the "Language Poets" and The New York School, although unlike the former she does not promote a neo-Marxist view of textuality and, unlike the latter,her ironies have a more decisively social edge. Typographical experimentation in much of her work may be traced to the influence of the Black Mountain "Projectivists," but otherwise the poems display a humor and a tolerance for quasi-anarchic linguistic play that are distant from the poetic effects of Olson, Duncan, Levertov and company.

Considering poems originally collected in Not Be Essence That Cannot Be (1961), published a year before John Ashbery's tremendously disjunctive The Tennis Court Oath, I conclude that Owens could have provided the precursor texts for the "Language" poetry of the following three decades just as easily as the celebrated Ashbery. Take, for example, the variously fractured sentences of "Up Up on the Disorders of the Hairs":

The least be be oaklike colorless. Or. Or the

Sweat ducts hither hither Come. Up the nostrils

Tangled incredible. On this genus brass. Yellow.

Being touched hither hither hither hither flat-

footedness, focus on this genus brass. Yellow.

Yellowish in the fe-male. In the huckleberry.

By the dry withdraw-al.

In this stutteringly reiterative passage, the poet begins with a kind of resistance to visual description or a severe limitation of it, then registers the possibility of alternative perception, moves to a desire to "focus" or "touch" sensory experience, however "tangled" or "incredible," arrives at a general naming of color that identifies a gender-split ("fe-male"), and finally retreats to a further reticence.

A 1972 poem, "The Voluminous Agony of Karl Marx," showcases Owens' gift for hyperbolically satirical dramatic monologue: "I am the coming judgment! Economics!/ My veins are religious with economics!" Her caricature of Marx—or perhaps one of his followers—gives us a resentful neurotic who hates "the passage of time without revolution," feels "abused by/ historical forces," as though suffering viscerally from his own perceptions, and is anxious about his distance from the proletariat: "Let me play Karl Marx! Let me play a workman!/ I have got big calluses! Boils! Calluses! Boils!" This "Marx's" materialism makes for an anti-idealism so fueled and clotted by resentment against his personal "fate" and generalized rage that, in its very pyromania, its intolerance for ideas and conventional religion, it turns ironically into another idealism: "Yahweh! Yahweh!/ You gave me boils! A family to support./ Six mouths to fill up with groats and milk!/... . I want to write the philosophy that will/ burn down all other philosophies! I want to/ kill all those who see ideas! Not economy!"

Lest one assume that the fun Owens has at Marx's expense is satire in the service of global capitalism's advance, the "Wild-Woman" poems, collected ten years after "The Voluminous Agony" articulate a lively critique of what Eisenhower dubbed the "military-industrial complex." Here is the "projective verse" of "Wild Woman & the Thinking-on of Putrefaction":

the TOTAL MASS

to bombing &

construction

an eagle flies over

the ravages of Frozen waste & disappears

to warm regions

the approach

to home &

the land

the wealth

of Great Rivers

the winging

system

readily

exploitable

made into desert (interior)

vileness in industry

consumption in Pacific

Ocean a hostile

climate makes birds

sluggish.

The typographical play enables ominous images and critical abstractions to hover—like the poisoned birds.

In her work of the mid-eighties, Owens' meditative propensities come to the fore. "Tension," charting the relation of kinesthetic functioning to internal visualization, considers how "consciously or unconsciously/ the act of tensing a muscle/ has a tendency to occupy the brain." When a woman's "calf muscle/ cramped perversely," it made her "lose her balance and," when she fell "from the ladder the month before," there was "an image in her mind/ of the sinews of cats tensing/ hunting." Exploring the irresistibility and danger of generalization and losses of cognitive equilibrium, "The Wood Fence" features a marvelously deranged syntax presenting a film clip of "history" as a horde of generalizations rushing to accomplish something big, and bumping into one another:

this indispensable you need your

project if it grows older you stick

it into the illustrated guide with

a grain of salt you take history and

character size yourself up make a

microscopic assumption time immemorial

says you're right once learn one thing

at a hundred times seven sags down the

old poet's eye-lid when it rains.

Substantial selections from a long poem-in-progress, Luca: Discourse on Life and Death, which, "begun in 1988, is an ongoing meditation on the theme of Mona Lisa and Leonardo," open New and Selected Poems. Leaping from image to image, meditative fragment to fragment, and continually returning to slippery motifs, Luca cogently evokes the tenuousness of strivings for aesthetic perfection and the model's role as co-producer/victim of the visual text: "masterpiece charred/warped deranged curvature/ slanting dissolving one can sit/ wondering in the same position/ thinks Mona nailed into space/ .... during painful days of sitting/ smirking rolling my throat/ the whole meaning bursts." While Mona Lisa "was like a woman who awoke too/ early/ in the darkness in order not to/ be changed," processes of painting and interpretation are inevitably and continually seen to be convulsed by uprooting, disorienting transformations, often violent ones, as "Lenny," possessor of a "fibrous memory," keeps renewing his determination: "without beginning the enigma/ preserves details the interruptions/ into dozens of edges screws Proto-/ types together.. slowly I abandon courage said/ the disciples posed like young/ peasants circuling a bonfire/ Da Vinci squares his hands."

The diversity of witty, bold, imaginative, and incisive poetic experiments in New and Selected Poems should provoke more substantial attention to Rochelle Owens from scholars who produce histories of contemporary avant-garde writing and from the readers who sustain it.

—Thomas Fink

It is difficult to imagine that Owens has been plowing her rows since 1961. For more than 35 years, she has been at the center of America's avant-garde, one of the few women in those circles, and this fat new volume gives readers a generous glimpse of what she has been about. Well known for her plays, which have won five Obies, she is a poet first and foremost, the author of 16 collections, the best of which is included here. That Owens writes for the stage should come as no surprise to those who know her poetry. Her work is all about voice and voices, real and imagined, historical and internal. She can bring John Wayne and Catherine the Great into the same poem, invoke Marx and Stalin, and balance lines with W.C. Williams and W.C. Fields and, in an excerpt from her mega-work-in-progress, Mona Lisa and Leonardo. It is perhaps other voices, though, the unidentified and unrecognized, that have the most say. From the perspective of invisibility and anonymity, Owens exposes the real world, the natural and unnatural. There's never a dull moment. Important for any large or modern literature collection.—Louis McKee, Painted Bride Arts Ctr., Philadelphia

The New and Selected Poems of Rochelle Owens are an eruption of ferocities, spells of amazement and hovering wrath, invasion of beginnings no immunity can insulate. For me the Luca passages, Discourse on Life & Death conjure up presences in waiting, let loose here, the year 1519 shaped in these numbers, the year of Leonardo's death, and Cortez's entrance into Tenochtitlan, sweeping us up into the co-inflations of this moment and brought forward as a "shadowy bride" demanding an intelligence that might convert us to other destinies.