Poetry Books

The Aardvark Venus: New & Selected Poems 1961-2020

Hermaphropoetics: Drifting Geometries

Out of Ur: New & Selected Poems 1961-2012

Solitary Workwoman

Luca: Discourse on Life and Death

New and Selected Poems 1961-1996

Rubbed Stones

Black Chalk

How Much Paint Does the Painting Need

W. C. Fields in French Light

Constructs

The Joe Chronicles Part 2

Shemuel

The Joe 82 Creation Poems

I Am the Babe of Joseph Stalin's Daughter

Salt and Core

Not Be Essence That Cannot Be

Hermaphropoetics: Drifting Geometries

2017, Singing Horse Press

What I love about Rochelle Owens' marvelous long poem Hermaphropoetics/Drifting Geometries is that the poem welcomes me into a visual landscape where I as reader awaken to a magical world of the poet's design.

By the title of the poem alone you know you're in an exotic place. It is a place where sex is everywhere as all over the hermaphrodite's body, where the eye attunes to second by second shifts with the richness of kaleidoscopic colors.

Owens opens the door and invites you in with her precise language which tickles you into submission to her vision.

What is Rochelle Owens' vision?

It may be something too terrible or marvelous to state in a declarative sentence.

Owens' images are rich and her words toy with what can emerge from the reader's depths of being so that reading the poem is a collusion between the writer and the reader.

Owens stages her poem as on a movie set and because her images are so vivid, the reader experiences the poem with the intensity of a film goer captured by the movie screen.

How does the poet achieve this magic?

I shall write about this in my second installment of my review of Rochelle Owens' Hermaphropoetics/Drifting Geometries.

What is Rochelle Owens' vision in this poem?

It is to see the truth of the moment. Because of Owens' mastery of language, the reader sees clearly what is present. One of the recurring images of the poem is:

"The master photographer

alters perception"

Through Owens' trompe l'oeil the reader becomes the master photographer capturing what is set on the page in the mind's eye.

It is this strange alchemy of identity which to me is the genius of the poem. Rochelle Owens frees the reader to enter and experience the poem in the most intimate way.

How does she achieve this magic?

To quote a Kafka epigraph:

"Nothing can be so deceiving as a photograph. Truth, after all, is an affair of the heart. One can get it only through art."

Rochelle Owens is a sorcerer who calls upon the elements of the sensual world and opens all orifices to the interior world of the spirit.

Some of my favorite images and language from the poem:

"playful the unborn babe

in its amniotic sac"

"sinuous the rhythm beneath

the skin"

Insectoid

pollack-like

warhol-like

calder-like

RUINSCAPE

out of the mists of Cumae

out of the hole of Baudelaire

Scholars can find a treasure trove in this poem to analyze and debate.

Enthusiasts like myself discover things about being alive we never knew before.

That's all because of

Hermaphropoetics/ Drifting Geometries by Rochelle Owens

Rochelle Owens: Fragmentations and Unifications of Vision

Rochelle Owens has made a name for herself for her avant-garde plays and her poetry which take the reader into uncomfortable territory of taboo, flesh, violation, body fluids, and life. The graphic nature of her imagery has been the "shiny object" that generally captures the critic's attention, and unfortunately the sometimes shocking nature sometimes blinds them to the work's philosophical complexity and her subtle commentary on how we see reality, beingness, and becoming in a world that contains intersections of imaging technology and the body / person herself.

Hermaphropoetics: Drifting Geometries is a collection of poems describing a series of stills in videos depicting the same object (a person). To summarize, Hermaphropoetics is about the fragmentation of unity and/or the deconstruction or deliberate disassembling of unity.

The various poems illustrate how there are many ways to see the same thing. Owens takes a series of still photos that comprise a video and describes them individually. However she does not say where exactly they fit within that series of images. Observing one still after the other creates a historical continuum from the first videographers, the Lumiere Brothers, to today's high-tech videographers. Rochelle's emphasis on the fragmentation of video and the dissolution of a recorded event also brings to mind today's more or less omnipresence video making abilities in the form of smart phones. We are reminded that the technology has made us tend to forget that video still is a series of single frame images.

The parallel with language is clear. Language creates a reality and the words (parole) are the individual stills. Take them out of sequence and the reality they create is mediated—always—by the reader / audience. On a cellular level we like to think that the raw images create reality.

Rochelle Owens shows us that once you stop the flow—image after image after image, you suddenly find yourself unable to actually connect with the reality until you place it within a narrative which by definition includes language. That language does not necessarily have to be verbal but there is a language nonetheless.

So Owens considers video stills. We can say that they must exist in a certain order to gel into meaning(s). The stills constitute the words and the parole of the grammar of visual discourse.

The sequence of video stills demonstrates that all meaning is in essence a construct that is constantly being deconstructed and reconstructed.

The repetitions of images are like incantations. They rip open and expose the heart and a sense of life. When Rochelle discusses exposed flesh she's also talking about the private laid bare in the raw, painful moments where one is subjected to the indignity of the gaze.

The camera is invasive. It creates in the subject a profound level of humiliation that has to do with one's autonomy. The individual in fact is a being, and that beingness is suddenly stripped away and placed in the hands of the individual who has the capability of ordering the series for sequences of images and also to create a narrative that describes what is happening.

In addition to creating sequences, Rochelle Owens creates fragments and in doing so reveals how it is possible to cast the meaning-making process into indeterminacy.

In doing so, she seizes upon the nature of what it is to create art. There is the artifice of becoming and the frames seem to be becoming something, but the frames can never become anything without the reader's externally imposed narrative.

We crave explanations and we want a sense of the whole but the parts do not and cannot add up because the video stills that come together to make a narrative are inadequate to keep the mind of the post-postmodern reader in a single track.

The objectification of that frozen moment of death, nakedness, vulnerability and exposure is what Rochelle Owens has created. Owens's avant-garde plays and poetry have always had a way of making reader feel vulnerable and awkward. On one level, that emotional response is in part about the process of coming to grips with indeterminacy.

The camera is in essence the technology of object-making. The accompanying consumption occurs by creating the tools by which the reader enters and then slowly moves into a state of self-fragmentation. Self-fragmentation is painful at first, but after 10, 20, 30, 40, and 50 repetitions profound desensitization occurs and one enters into almost an almost trance-like state.

Each camera technique offers its own slow trajectory. Life's puzzle pieces are meaningless when scattered out of order. Repetition, despite J Hillis Miller and his notion that there is no meaning without repetition, does not necessarily hold water. Simple repetition does not make meaning. Patterns are patterns.

The assignation of value that is to assign value to the pattern—whether denotative or aesthetic—is arbitrary. Nevertheless, there can be a sense of urgency if the pattern has some kind of consequence in the phenomenal world, such as being run over by a car or the likelihood of certain aggressive behaviors of dangerous people.

Rochelle Owens shows the absolute arbitrariness of life force elements that we generally consigned to the sacred.

That Dionysian Jazz: on Hermaphropoetics, Drifting Geometries by Rochelle Owens

Amy L. Friedman

A lone figure sits on a stump. This is the cover image of Rochelle Owens's newest poetry volume, Hermaphropoetics: Drifting Geometries. With slightly downcast shoulders and a pensive air, it could be Estragon, or Vladimir. It is, in fact, an image titled "Person Who Is Sitting On A Tree Stump," and as the first thing encountered as an introduction to a long poem which relentlessly challenges the categories of gender and sex, notions of ontology, and the expectations of linear narrative, the image is apt.

Work by Rochelle Owens should bring to mind an instant association with groundbreaking writing, if one has seen or read her Off-Off-Broadway plays such as Futz and Istanboul or read her book-length poems. She should be immediately tagged as an avant-garde artist, one who challenges, reinvents, innovates. A long time ago, in 1981, Rochelle Owens was asked to create a writer's statement to contribute to a collection of manifestos about the arrival of a new poetics. She wrote memorably and incisively: "Because I am bored by traditional, conventionalized and fossilized systems of writing poetry and plays, they are useless, I demolish them." It is not surprising that critic and scholar Tim Good refers to her as a revolutionary. I rather think she should be commissioned as a demolitions expert, first-class.

At the time Rochelle Owens began publishing her poetry in Diane Di Prima and LeRoi Jones's Greenwich Village journal, Yugen, cultural observers elsewhere were noting, sometimes tepidly, that literary journals and performances were breaking boundaries, and reflecting a degree of innovative change in the fringe arts scene. But Owens was never interested in anything as milquetoast as mere "change." Her fearless focus was always on driving the cutting edge, and on the avant garde as something that shapes its own reality.

It is justified to find in Owens's Hermaphropoetics some echoes of her powerful earlier epic book-length poetics works, The Joe 82 Creation Poems (1974) and The Joe Chronicles Part 2 (1979). In these works Owens is investigating a gender-undermining approach to language, which in Hermaphropoetics becomes a front-and-center concentration on a principal hermaphroditic figure, for whom gendered language is split, hyphenated, and augmented. In the earlier work, The Joe 82 Creation Poems, there is a major figure, the Wild-woman, adjacent to the poem's Wild-man; these two are at times in tense juxtaposition. The Wild-woman possesses paradoxically "masculine" traits which nonetheless enable her to flourish. The Wild-woman is resilient, imaginative, assured, sexual, and energetic, and at one point she names herself a "Woman-Abraham," empowered to establish a cult, to inspire followers, to make an impact, as a leader who pronounces on rites of naming and creation.

Hermaphropoetics in some ways continues these lines of investigation, but in a markedly different and singular way; the masculine and feminine have now totally fused. More arguably happens and has happened in the long poem than in the Joe poems, but less is explained.

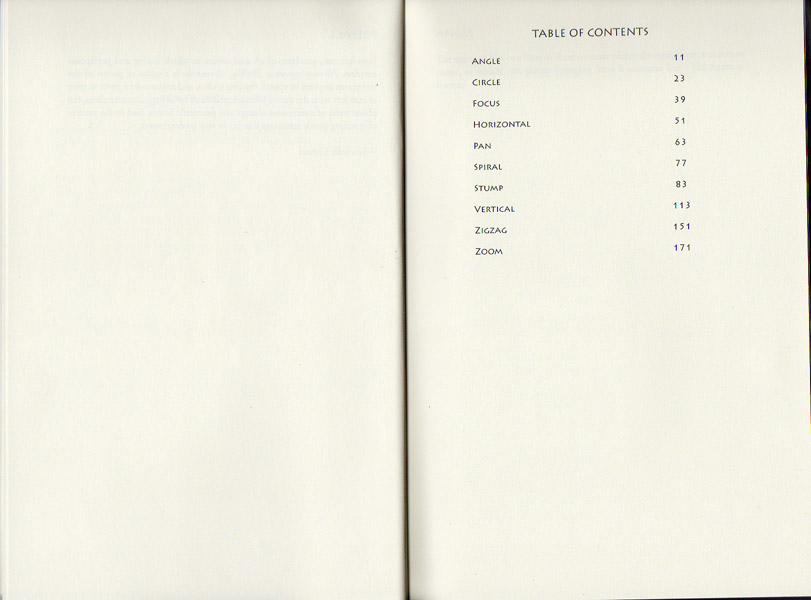

Hermaphropoetics is a work of experimental and ethnopoetic practice, crafted in short, repetitive strophes; each strophe is but one, two or three taut lines. The text repeats an overarching narrative of an isolated figure, stump-seated. Dramatic events have taken place. The scene is perhaps being filmed, and in the poem a camera takes pictures, and whole sections of the work are named as both elements of geometry and cinematography: "Angle," "Focus," "Spiral," "Zoom." The camera angles suggest shifting perspectives as well as the poet's term, "Shifting Geometries." Violent things have happened, but a tide of phrases of fecundity nonetheless throbs throughout.

a hermaphrodite

captured after the siege

a hermaphrodite

emptied of allegory

seated on the stump of a tree

his soaring paper thin

shoulderblades

The master photographer

focuses the lens

The camera zooms and pans

the dome of her skull

his earlobes...

his legs collapsing under her

his mouth waters taste buds pulsate

a flow of hormonal forces

hypermasculine hyperfeminine

murderous sex cells

In the central action of ethnopoetics, a scribe respectfully records the utterances which comprise the core of a culture. The activity is intended to provide a record of performative aspects of a cultural community, to preserve the order of words as they are performed, and to note also the silences and the repetitions which might make a ritual utterance mystifying to a cultural outsider. Thus the chants of First Peoples can be inscribed without misrepresentation, and spared any inappropriate editing to impose a "neater," or euro-centric, or non-native, linear-narrative form. As an aesthetic, creative practice, ethnopoetics defies any imposed hierarchy of narrative line. Compulsory narrative may even be deemed suspect. And in Owens's Hermaphropoetics, we return inexplicably to the repeated narrative of the mysterious seated deaf-mute hermaphrodite, but as the figure seems more familiar as the text returns to his/her narrative, the descriptors shift and mutate. Sometimes it's "her platinum blond curls/bringing millions to their knees" and other times it's "his platinum blond curls/bringing millions to their knees," but always the power of the poetic line intensifies. Owens' writing in Hermaphropoetics has the weight of a national creation myth, or a projected future cultural originary story, with rhythmic phrases which, repeated, become choruses in celebration of a significant poetic mythos. But if that sounds in the least ponderous, then note with celerity the linguistic playfulness, the sharp imagery, and the wide-ranging, even mischievous cultural references which remind one that no poet writes for as many decades as Rochelle Owens has without also having fun.

In this story

ripening on the vine

so to speak

in this story

a warhol-like playfulness

a vinyl fruit of desire

l'amour impossible l'amour

possible

in a dream of a hermaphrodite

in silhouette

her hollow bones

glow under a black light

magnetic his hollow bones

elegant the fusion of bird

and human

her soaring paper thin

shoulderblades

his sculpted pelvis

In the social psychology field of career construction theory, counselors ponder the stories that underpin how a professional career unfolds, to look at how an individual makes sense of the self-identity that evolves from an occupation. Transposed to the milieu of poets and playwrights, they might ponder what patterns and periods comprise the whole of a significant literary career, and how this impacts readers' judgements about individual works over time. An intriguing query develops about whether one might read "early" or "later" works by the same author in different ways, or with differing expectations of the gradations of "importance" that critics done out when impacted positively by a work. Hywel Dix thinks about this a great deal in his recent monograph, The Late-Career Novelist: Career Construction Theory, Authors and Autofiction (Bloomsbury 2017), arguing "that whereas much critical attention has been devoted to establishing the idea of a major phase and hence to the transition between early and mature works of an author's career, the late stage has received comparatively less attention." Dix's overall focus is on a "rigorous critical interrogation and provisional clarification" of what a "late" stage in an author's oeuvre might be discussed or constructed as, and why. Dix takes issue with the way the idea of a "literary and artistic decline wrought by the process of aging" remains "common and hence unchallenged" in literary biographies, critical reviews, and retrospective writing about writers. He concludes that "to challenge the idea of distinct major and minor phases is also to challenge a cultural and social hierarchy based on age." Dix is accurate that there is a prevailing and quite dominant model, in which chronologically later work is expected to be a revisiting of a writer's prior themes and subjects, as if later work presupposes the exposition of the lifetime of worthy habits that the writer has engraved into the writing practice of a career; the successful artistic path is etched and then repeated. The assumption is that the distinguished writer, Dix continues, returns to techniques or forms for which he was celebrated, or she was recognized. The flaw in apprehensions of entire authorial careers is thus that there is little to no expectation of significant artistic development in work which is categorized as chronologically "late." And there is also scant appreciation, nor interpretive space allocated, for artistry which will never just follow on, but which will always veer anew.

Dix wants instead to interrogate any assumption of a "career high point and subsequent decline," and to assert instead that the way diverse stages of "a given authorial career are constructed" is in a manner which is simply specific to that career. Obvious, perhaps, but a stance which enables readers to divest expectation and to even read with a sense of suspense. The most crucial elements to alter in critical perceptions, according to Dix, are to bypass readings that seek "conformity" in a writer's output and to consider instead the criteria of "deviation and innovation." Edward Said put it another way in his posthumously published work, On Late Style: Music and Literature Against the Grain (2005), in a discussion about Theodor Adorno's comments on the ways in which Beethoven's final symphony, The Ninth Symphony, and final five piano sonatas convey both newness and "the irascible gesture" towards critical assumptions and expectations. Edward Said notes that regardless of our cognition of Beethoven's personal straits when he composed music in his later years, one can't reduce these later works "to the notion of art as a document" about his state of being, or to a reading of the musical material in which personal history "breaks through" and takes over. "Late style," Edward Said continues, "is what happens if art does not abdicate its rights in favour of reality." Mature, fulfilled, deviant, innovative, and even irascible style is achieved when "late" is not acknowledged at all, as when the avant-garde artist continues to redefine his/her reality.

painterly images

cells forming cartilage

when the subatomic

particles when

when frame by frame

breakdown when

when burned

by its light source when

when at the edge

of the village when

when four bearded elders

circle when

when the bride holds

a mirror when

when she falls

to the ground when

when the village on fire

appears disappears

With these deceptively straightforward, repeatedly deployed syllables of "when," the poet completely and efficiently disrupts the line. She embeds suspense and prompts silent readers to pronounce the poetry aloud, to lift the words from the pages, and to join her, Rochelle Owens, avant garde artist, in making that Dionysian jazz.